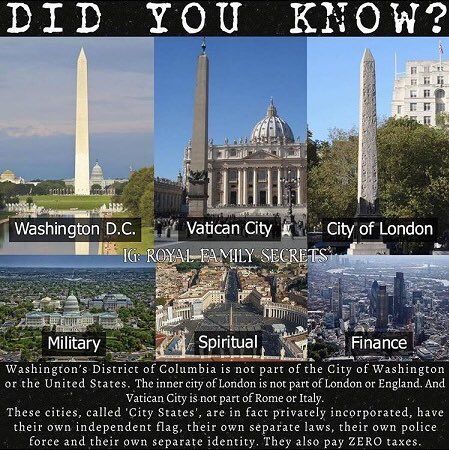

Gog and Magog from the Old British Empire – The City of London holds an annual parade centered around two giants called Gog and Magog, heralding them as guardians of London. Brutus, who was the first inhabitant of Britannia now being England. founded it and named it New Troy). Today not many people know that London was once called New Troy.

The City of London holds an annual parade centered around two giants called Gog and Magog, heralding them as guardians of London.

The city now called London was at first called Tro Newydd , or New Troy , and by Latin writers Trinovantum.

Gog-Magog, a british giant, said to be 12 cubits high, an image of which stands in the guild-hall of London. (BAILEY, 1735.) For a description of the two gigantic figures in the city of London, usually styled Gog and Magog, see European Magazine; vol. lviii, p. 116.

Gog was prince of Magog, according to Ezekiel; Magog being the name of the country or people.

We cannot pledge ourselves to the truth of old Caxton’s narrative, but we are quite certain that Gog and Magog had their effigies at Guildhall, in the reign of Henry V. The old giants were destroyed in the great fire (in 1666) present ones, fourteen feet high, were carved in 1708 by Richard Saunders.

Even nations join the pilgrimage. England’s fight for identity in postwar Europe occurs alongside the birth-pangs of Israel. Fellow questers for Zion, the two nations league politically, militarily, and economically. The new Jewish state, further-more, with its overseas markets, has already fallen into the destructive pattern of imperial England. Nlagog, fearing that Israel will overreach herself as England did, warns an Israeli friend, “I don’t want Israel to become a little British Empire.

Concerning New Troy/Trinovantum one can mention the case of King Belinus who “caused to be constructed a gateway of extraordinary workmanship, which in his time the citizens called Billingsgate, from his own name. On the top of it he built a tower which rose to a remarkable height; and down below to the foot he added a water-gate which was convenient for those going on board their ships” (Geoffrey of Monmouth 1966: 100). In his Brut, Laʒamon remarks that “this tower bears this name [Billingsgate] today and for ever” (1. 3022), which is right since Billingsgate is still today the name of one of the 25 Wards of the City of London.

New Troy in Medieval Art

London was not only referred to as New Troy in poems and chronicles. This name was also used in illuminations and maps. British Library fifteenth-century manuscript Harley 1808 contains (fol. 30v) a fullage illumination showing Brutus’s landing at Tomes, the killing of the giants. and the building of the fortified New Troy.

A beautiful view of London worth mentioning is a pencil drawing to be found in a genealogical roll of 1485 (Ms Bodl Rolls 5) preserved at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. London is there explicitly designated under the name of New Troy.

The best-known and most outstanding illustrations are certainly Matthew Paris’s maps. Matthew Paris was the main chronicler in the mid-thirteenth century at the Benedictine abbey of St Albans.

In the opening folios to the first volume of his universal chronicle, Chronic° majors, lies a scrim of itinerary maps which tract the mute from London to Apulia and eventually to the Holy Land in a strip-like format. Matthew Paris adorned each stage of the route with picturesque town symbols and short inscriptions.

This pictorial itinerary is to be found, for example, in Corpus Christi College Library Ms 26. Its first image is that of London with the following caption in Anglo-Norman (the French language spoken at the time in Britain): –

la cite de Lundres ki est chef dengkterrc. Brutus ki premere inhabita bretainne ki ore est engletenc la funda c lapcic troic la nuvcle” (the city of London which is the capital of England. Brutus, who was the first inhabitant of Britannia now being England. founded it and named it New Troy).

The vignette shows an oval space divided into two parts by the Thames. Within the city walls St Paul’s Cathedral (sena poi). the Tower (a fur). and Westminster are represented. Other sites are simply named: la triniti (Holy Trinity at Aldgatc) or le punt de Lundres (London bridge).

Across the river, the names of Lambe: (Lambeth Palace), Sanely (Southwark) can be read. And in the back-ground the names of three gates are inscribed on the city walls: Ludgate. Neugate (Newgate). Crupelgate (Cripplegate). Even further back a church is drawn, it is Binnunetcee (St Mary-Magdelen Priory in Bermondsey).

New Troy After the Middle Ages

The good fortune of Brutus and of the foundation of New Troy went on beyond the Middle Ages. The Trojan myth had become national property and heritage. It was now pan of the English iden-tity and literary tradition. In 1577. Raphael Ilol-inshed and Abraham Fleming reminded their readers that

Here therefore (Brutus/ began to build and lay the foundation of a cite. in the tenth or (as other Minket in the second yeast after his arrivall. whkh he named (smith Gal. Mon.) Troinouant, or (as Llhoyd with) Troincwith. Mat is. new Troy. in remembrance of that noble citie of Troy from whence he and his people were for the greater part descended. (liolinshed and Fleming I 8.07 (eke-ironic version])

Edmund Spenser too mentioned at length the early times of Britain and the foundation of London in his Book III, song IX of The Faerie Quecnne (1589-1590 and 1596), “for noble Britons sprang from Trojans bold. /And Troynouant was built of old Troyes ashes cold” (Spenser 1908 [electronic version)).

The myth went on with John Milton’s History of Britain (1670), Hildebrand Jacob’s Brutus the Trojan: founder of the British Empire: an Epic Poem (1735). William Blake’s “0 sons of Trojan Bru-tus”(Poetical Sketches. 1793). or the anonymous The Romance of Brutus the Trojan (1860).

In the twenty-first century, several fantasy novels for children feature Brutus as hero. Today not many people know that London was once called New Troy.

Yet. Brutus has not totally disappeared from the British capital. Every year two enormous images of the (benevolent) giants Gogmagog and Corineus (now known as Gog and Magog) are carried in the procession of the Lord Mayor’s Show of the City of London.

The practice dates back to the reign of Henry V (1413-1422). The official website of the show gives a detailed summary of the tradition conclud-ing that “Gog and Magog symbolize one of many links between the modem business institutions of the City and its ancient history.”

The Lord Mayor’s Show 12 November 2022

https://lordmayorsshow.london/history/gog-and-magog

The Lord Mayor’s Show 12 November 2022

https://lordmayorsshow.london/history/gog-and-magog